Earlier this year, the Bulgarian government’s attempts to shut the Republic of Macedonia* out of the European Union (EU) fueled a storm of ultra-nationalist statements from Bulgarian officials, and dissatisfaction with the EU amongst Macedonians. From the beginning, Macedonia’s process of accession to the EU has been marred by political considerations from neighbour states acting as a façade for legitimate considerations to deny admission. The dialogue between Sofia and Skopje has been unfriendly to say the least and does not bode well for the future of the EU in the Balkans.

Since gaining statehood in 1991 after the fall of Yugoslavia, the then-Republic of Macedonia struggled with Greek vetoes to their entry into the EU and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) for nearly three decades. Despite Macedonia being forced to take on the temporary name of the ‘Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia’ in the promise of entry, the vetoes persisted. In 2011, the vetoes to NATO accession were deemed a violation of the Interim Accord of 13 September 1995, per the International Court of Justice.

The motivations behind this, concern the name ‘Macedonia’ which describes both the country and the northern region of Greece. The use of the same name for national and subnational entities is not unheard of; consider the country of Azerbaijan and the region of the same name in Iran, or the country of Luxembourg and the province of the same name in Belgium. While not unprecedented, it was treated as such for Macedonia.

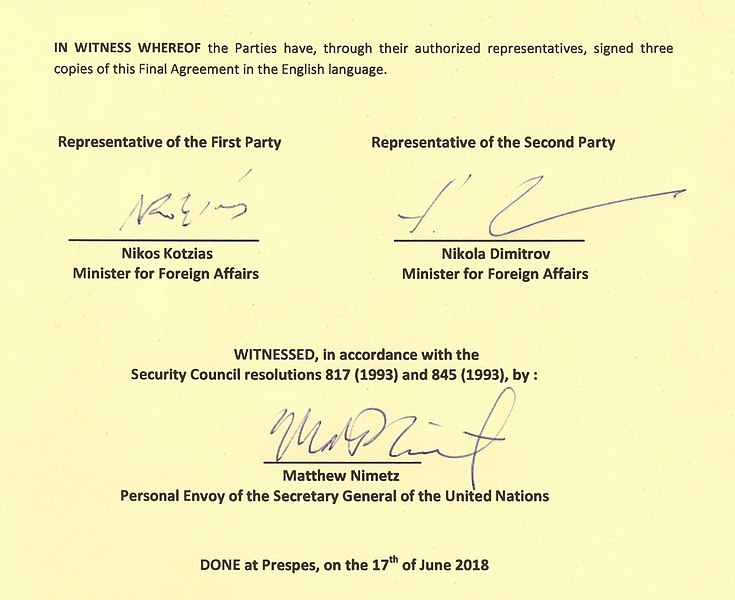

In 2018, the Macedonian and Greek governments put the issue to rest for the time being with the signing of the Prespa Agreement which renamed the country ‘North Macedonia’. For different reasons, the Agreement was deeply unpopular on both sides of the border. Despite this and its pseudo-democratic reception in Macedonia, the decision was official. With the support of Athens, Skopje looked east toward Sofia. To gain the support of Bulgaria, officials created a joint historical commission (alike the one established through the Agreement with Greece) which led to calls for historical revisionism. Unsurprisingly, the commission did not achieve consensus.

Bulgaria blocked Macedonia’s EU accession talks in 2020 over cultural concerns. Such reasoning was antithetical to the Agreement on Good Neighborly Relations signed between the two states in 2017 which hoped to reaffirm the sovereign right to self-determination which exists outside of historical considerations. The absurd demands made by Sofia include recognizing the Macedonian language as Bulgarian – a matter non-negotiable in Skopje. These demands come as Bulgarian officials openly make inflammatory, anti-Macedonian statements. This does little to soothe Skopje’s worries over the veto. In the fall of 2020, Bulgaria’s Minister of Defence, Krasimir Karakachanov, stated “If necessary, I will send the engineering regiment to help me remove [Macedonians] faster or I will send them from my organization VMRO, they will remove them in 24 hours” [translated]. In the spring of 2021, while the Bulgarian government sought to rile up support among their ultra-nationalist voters and subdue discussions of corruption, they were burning bridges with Skopje.

This October, dialogue opened up again and is conditioned on six demands by Sofia which must be agreed upon by November. One of these demands includes naming Bulgarians in the Macedonian constitution. Bulgarian President Radev insists there are 120,000 Bulgarians in Macedonia while the 2002 Macedonian census counts 1,500. Desperate to travel without restrictions, some ethnic-Macedonian citizens of Macedonia have taken out Bulgarian passports since Bulgaria has been an EU member since 2007. Sofia believes these passport holders should self-declare as Bulgarian within Macedonia. Skopje clarifies that all citizens in their territory can self-identify as they choose.

Moreover, Sofia requires a consensus to be reached under the joint historical commission. However, one of the historical disputes include Sofia’s claim that Bulgaria was never an Axis occupying force within Macedonia’s territory during the Second World War. Despite such statements being overtly untrue and dangerous revisionism, Macedonian Prime Minister Zoran Zaev controversially stated last year, “We already replaced 20 plaques on which it was written, ‘Bulgarian Fascist occupier’. This is not true – Bulgaria is not a fascist country; it is our friend”. This only brought further division as Sofia prefers the term “Bulgarian administration” instead of the compromise offered by Skopje of “fascist occupier” – not directly naming Bulgaria.

Another of Sofia’s demands includes rehabilitating victims of communism. This refers to the Bulgarians killed during the Second World War in Macedonia by the anti-fascist communist-led resistance, and their supporters. While the Yugoslav secret police undoubtedly targeted pro-Bulgarian sympathizers, they also targeted those who were pro-Macedonian. Both were viewed as a threat to Yugoslav unity.

Sofia additionally demands non-interference in domestic affairs. In Skopje, this is understood to mean the country must not advocate for the rights of ethnic-Macedonian citizens of Bulgaria – a minority Sofia does not recognize. In fact, Bulgarian officials have repeatedly trampled on the rights of this minority group to self-identify and register their political or cultural organizations. The European Court of Human Rights has, on numerous occasions, found Bulgaria to be in violation of Article 11 of the Convention highlighting the right to peaceful assembly and freedom of association.

In response to these new demands, Zaev stated “The EU has to move from words to action. If the EU does not act, the disappointment among the region’s citizens will cause serious and irreparable damage to the great European idea of community and cooperation”. Evidently, this is a high-stakes matter. Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama, whose country’s EU accession process is linked to Macedonia’s added “We have learned the hard way not to expect anything…”

Macedonia has yet to become a member of the EU since negotiations began in 2004. It is insincere to believe that negotiations between veto-holding states and states dependent on their backing will turn out to be fair. No other state has been forced to jump through the hurdles Macedonia has, and Macedonians are well aware. Indeed, EU apathy is brewing within this community. Those who once yearned for membership, now fail to see its value. Many Macedonians feel as though they have sacrificed an arm and a leg – is the head next? Macedonia cannot be a member state of the EU if by the end of this process of negotiation they are no longer a state. Thus far, Macedonia has been pressured to change its name, flag, history books, plaques and monuments, passports, and road signs – yet the list continues to grow and is soon to encompass Macedonian language and identity. *The author refers to the ‘Republic of Macedonia’ instead of the official title of ‘North Macedonia’ in an effort to not lend credence to the unconstitutional and undemocratic process that led to its renaming under the Prespa Agreement.