Tenth Anniversary Conference in Prague

Council of Members of the Platform of European Memory and Conscience Webinar notes by Hon. David Kilgour, J.D. (www.david-kilgour.com.)

12 Nov 2021

The implosion of the Soviet Union in 1991 brought freedom to almost 20 restored or new democracies in Central/East Europe after almost half a century of oppression. Then Russian leaders Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin supported national self-determination and democracy. The European Union added ten east-central European countries in 2004 and 2007 and almost 80 million European citizens to its union of democratic nations.

The transition from totalitarianism to democracy brought many changes to all these nations. Trade barriers were removed to allow freer movement of goods and services; many state-owned enterprises and resources were privatized (some into irresponsible hands). The economic performance of most of these nations has been good despite serious adjustment problems.

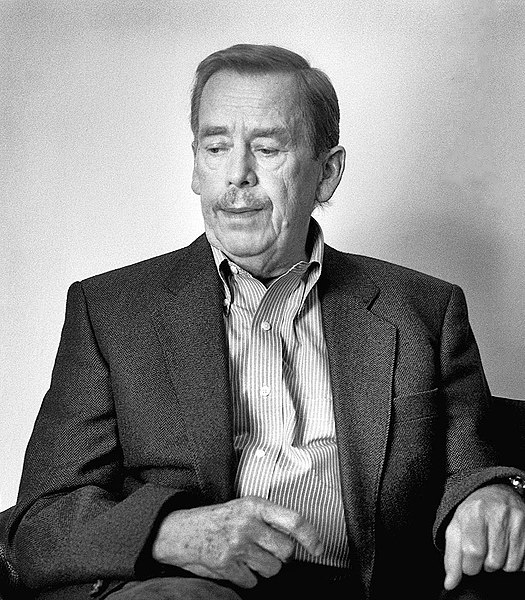

The end of despotism in Czechoslovakia, with the late Vaclav Havel moving in months from prison to the presidency in Prague, afforded an opportunity to carry out major political and economic reforms. The country, which later divided, has since seen flourishing exports and rising direct foreign investment.

What motivates some people to struggle for democracy? Havel asked of Czechs and Slovaks. “Where did (our) young people … (find) their desire for truth, their love of free thought, their political ideas, their civic courage?” The answer lies in the human desire to choose the types of societies we want to build for ourselves — ones grounded on values of dignity for all and the rule of law. The citizens of the Czech Republic in a national election recently removed the last Communists from their parliament after 100 years of presence by giving the party less than four per cent of their votes.

Baltic States

Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia have a combined population of only about 6.32 million, but are determined peoples. Once free, each wasted no time in aggressively pursuing economic reforms and integration with the rest of Europe. Between 2000 and 2007, the Baltic States had the highest real growth rate in Europe, ranging from 6 to 12 percent; from 2011 on, they have also done well.

Hungary and Poland

While now problematic, both transitioned to democracy and a market economy after 1990, despite significant losses in markets for exports and in subsidies from the former Soviet Union. In 1995, both privatized state-owned enterprises, cut their current account deficits and reduced public spending. Many suffered great hardship during the transition, but both economies grew about 4 percent in real terms between 2000 and 2006 and did economically quite well after 2010.

In short–and I’ve mentioned only some of your region’s nations– transitions were difficult, but in virtually all East and Central European countries, life appears to be significantly better now than in 1989. Despite current serious problems, the EU continues for most around a shrunken planet to be a beacon for democracy, human dignity, economic prosperity and stability.

Russia

An ailing Boris Yeltsin resigned his presidency in 2000 to former KGB lieut. col. Vladimir Putin, whose clear aim today is to destabilize democratic governments wherever feasible. The use of Magnitsky and other targeted economic sanctions might, however in time bring him or his successor to a collaborative engagement with the rule of law world. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) concluded that the average household disposable income for a Russian family in 2013 was (US)$15,286, ranking number 30 of the 36 OECD developed-economy nations. Today sadly, Russian incomes have fallen about 10% since 2013.

As COP26 meets in Glasgow, Russia has become mostly a petro-state. The economic/political focus of Mr. Putin and about 140 oligarchs has been on Russia’s oil and gas industry, keeping Europe dependent on Russian imports. The Crimea invasion precipitated a flight of capital from Russia in the first quarter of 2014 as large as US$70 billion. European peace remains essential if the Russian economy is to improve the lives of its citizens.

Yale history professor Timothy Snyder, author of Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, notes: “Ukraine (under Yanukovych) was governed by probably the most financially corrupt regime … which by the end of its rule was not only physically oppressing, but finally killing its citizens … (for) exercising their rights to speech and assembly”.

World chess champion and democrat, Garry Kasparov, wrote: “Vladimir Putin has twice during six years sent Russian troops across internationally recognized borders to snap off pieces of neighbouring countries, first in Georgia (South Ossetia and Abkhazia) and now in Ukraine (Crimea)…Trying to seek a deep strategy in Putin’s actions is a waste of time. There are only personal interests, the interests of those close to him who keep him in power, and how best to consolidate that power. If the West punishes Russia with sanctions and a trade war, it would be cruel to 140 million Russians, so instead sanction the 140 oligarchs who would dump Mr. Putin … if he cannot protect their assets abroad. Target their visas, their mansions and IPOs in London, their yachts and Swiss bank accounts. Use banks, not tanks.”

Democracies don’t oppress, segregate or terrorize. They value diversity, inclusiveness and respect for everyone by upholding the rule of law premised on citizen equality. They maintain independent judiciaries separated from legislative and executive branches. Reliance on a vigorous judiciary helps make it possible for minorities and marginalized groups to be equal members of society.

International institutions, such as the UN Human Rights Council and UN Security Council, should accord much more weight to human dignity and good governance around the world. We must all safeguard and enhance our own democratic practices and help strengthen democracies abroad, remembering always that it begins with each of us as individual citizens.

The number of full democracies across the world in the 1970s doubled by the 1990s because of efforts by many determined democrats. Today, their successors in many nations need to recognize that this governance model — democracy — is now in disfavour in part because it is seen to benefit “one per centers” disproportionately. The age of “robber barons” a century ago has become for many observers today an era of Big Tech tycoons, who appear to care little for their employees, fellow citizens or democracy.

Among a host of policy initiatives by governments that could help reverse negative perceptions of democracy are robust pro-competition legislation and enforcement, raising corporation taxes and banning off-shore accounts in tax havens, introducing election spending and donation limits, raising minimum pay and enacting effective whistle-blower protection.

Democratic governance can flourish across Europe and the world once again. It needs the active attention and care of all of us.