This is my first article written as President of the Centre for Eastern European Democracy (CEED). Our new Canadian federal non-profit organization dedicated to promoting liberal democracy in Eastern Europe is centered in Toronto and has ambitious plans for the days ahead. The purpose of this article is to comment on the origins of CEED, to share some history that may shed light on the value of its focus and to touch on the future.

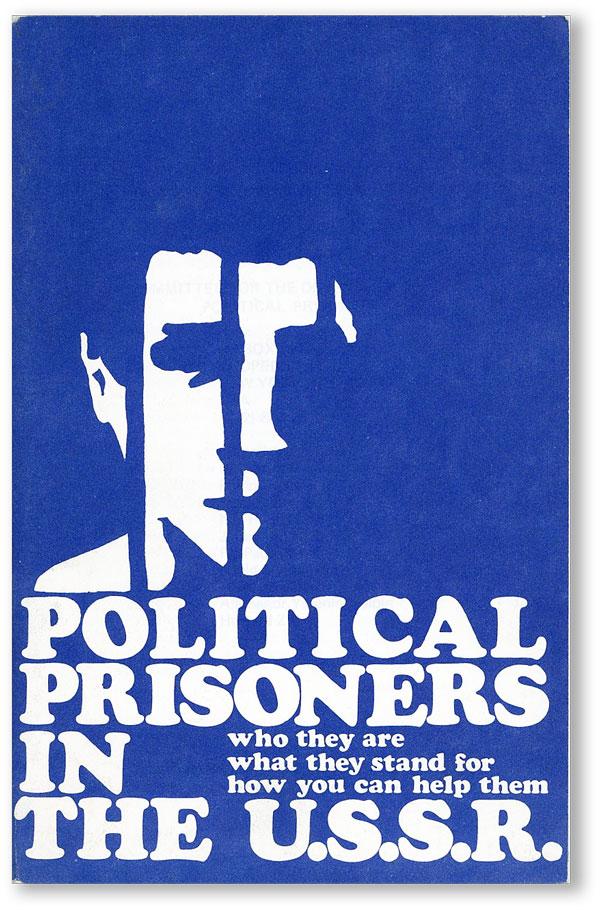

It can be argued that the origins of CEED can be traced back to the 1970s. The 1970s were a time of turbulence in the U.S.S.R. Having consolidated its power in Eastern Europe in the early 1920s, the Soviet Union crushed the Hungarian revolution in 1956, and then sent its tanks to put down the Czechs in the Prague Spring of 1968. By the 1970s, the U.S.S.R. was at its peak but political dissent was spreading. In the case of Ukraine, books like the Chornovil Papers written by Vyacheslav Chornovil, and Internationalism or Russification written by Ivan Dziuba, as well as the books of Canadian author John Kolasky about his experience in Soviet Ukraine, alerted many western readers to a growing dissatisfaction with life in the Soviet Union.

Around this time, word spread in the west about the arrest and imprisonment of Valentyn Moroz, a Ukrainian historian. A few volunteers in Toronto decided to ban together to form the Committee for the Defence of Valentyn Moroz. Among the members were Mykola Lypowecky, Oleh Romanyshyn, Genia Moore, Yuri Shymko, Andriy Bandera, Lada Hirna, Mykola Bidniak and a few others. In the summer of 1974, after Moroz undertook a hunger strike to be transferred out of Vladimir Prison northeast of Moscow, four Canadian hunger strikers embarked on a sympathy hunger strike outside the Soviet Embassy in Ottawa demanding that the U.S.S.R. release him. I was one of those hunger strikers. The hunger strike gained momentum when Senator Paul Yuzyk of the Canadian Senate and Yuri Shymko, one of our committee members, got in contact with Soviet human rights leader Andrei Sakharov, who began informing us about the plight of Moroz and other Soviet dissidents on a regular telephone basis. Meanwhile, more hunger strikes spread among young people in other cities across the United States and Canada supporting Moroz. The work of defending Moroz and other Soviet dissidents became mainstream.

At the same time, in New York, the Committee for the Defense of Soviet Political Prisoners was formed. Among the early members were Roman Kupchinsky, Stephan Welhasch, Adrian Karatnycky, Victor Rud, Marusia Proskorenko, Alex Motyl and Myroslaw Smorodsky. That committee took a broader view, focusing on advancing the cause of human rights in the Soviet Union as a whole while including Ukraine. It contrasted with the views of members of the Moroz Committee, who sought to focus on Ukraine and Ukrainian dissidents only. A meeting of mostly young Ukrainian young people involved in defending dissidents in the Soviet Union was held in Toronto and then in New York. A key issue arose. Should they work only in defense of Ukrainian political prisoners, or should they join the broader effort to help dissidents from all parts of the Soviet Union? No complete agreement was reached, but everyone involved did see the merit of working either way for the same goal of defending human rights and indirectly for Ukrainians, defending Ukraine as well.

In 1975 I worked as a journalist with the Ukrainian newspaper Svoboda assigned to cover the United Nations. With the help of Lubomyr Kwasnycia, I also did some freelance writing for Southam News Services in Canada and some other English-language newspapers. I was also hired by the World Congress of Free Ukrainians to head up its Human Rights Bureau in New York, with the hope of gaining accreditation for the Congress at the United Nations. I spent the next few years working at the U.N., but also joining and then becoming active in the Committee for the Defense of Soviet Political Prisoners.

The Committee was fed news of what was happening in the Soviet Union by Prolog and Smoloskyp, two research organizations, as well as by Amnesty International then defending political prisoners worldwide. In time, our Committee helped various dissidents from the Soviet Union, including Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, Pavel Litvinov, Valerie Chalidze as well as many Ukrainian dissidents like Leonid Plyushch, Valentyn Moroz, Danylo Shumuk, Nadia Svitlychna and others as they escaped the Soviet Union and emigrated to the West. The Committee recruited members from some other ethnic communities to join in its human rights work and joined forces with the Jewish Community in working together as well.

In many ways, this history parallels what CEED is doing today. The initiative for creating CEED was taken by members of the Ukrainian community, although the focus is on Eastern Europe given that most of the issues to be dealt with are mainly regional if not international. By virtue of the internet, and in view of the pandemic, CEED has created a web site which includes some key features—such as the Indices pages that rank countries in Eastern Europe based on certain key concerns like the rule of law and human rights, and the creation of a CEED Blog.

In CEED’s formation much discussion took place about what was the best way forward. Two views formed in that regard. One was to work with the academic community. The other was to work with the rank and file of Eastern European communities abroad. The discussion required clarifying the ultimate purpose of the organization and how it is to be run. In one case, the academic one, the ultimate purpose was education. In the community-based model, the ultimate purpose was activation. While the difference is slight, nonetheless, it was important to the formation of the organization.

So here we are. We have formed, we have a website and we have developed a plan for our work over the next few years. The plan includes maintaining the CEED website as a resource, publishing a blog, helping to hold seminars with Eastern European young leaders in Toronto in the summer months, and hiring a field worker to reach out to other organizations working in the same area. It’s a good start. We have learned to work with anyone who wants to work with us, so long as they believe in liberal democracy in Eastern Europe. We are looking forward to some great days ahead.